Antiphospholipid Syndrome

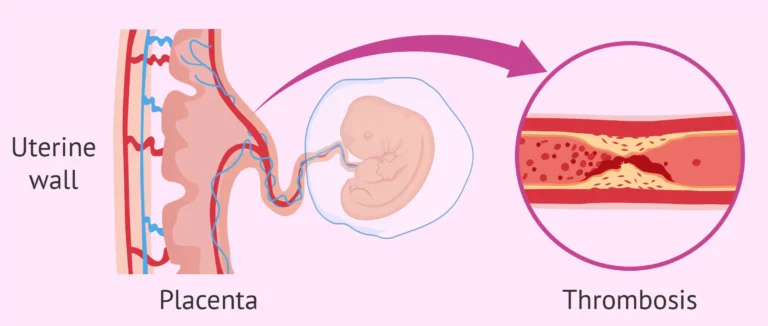

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), sometimes called Hughes syndrome, is an autoimmune disorder that increases the risk of blood clots (thrombosis) in both arteries and veins. It is a significant cause of recurrent miscarriage. The condition occurs when the immune system mistakenly produces antibodies that attack phospholipids, a type of fat found in all living cells and cell membranes, including blood cells and the lining of blood vessels.

Signs and Symptoms of APS

The most common signs of APS are directly related to the formation of abnormal blood clots. Doctors may suspect APS in a patient who has experienced:

- Thrombosis: Unexplained blood clots in arteries (which can cause strokes or heart attacks) or veins (like deep vein thrombosis).

- Pregnancy Complications: Recurrent miscarriages, especially after the 10th week of pregnancy, or premature birth due to severe pre-eclampsia.

Other common signs, which support the diagnosis, include:

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count)

- Livedo reticularis (a mottled, purplish skin rash)

- Persistent headaches and migraines

- In some cases, APS can be linked to other autoimmune conditions. For instance, a patient being evaluated for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) will often be tested for APS, as the two conditions frequently coexist.

Diagnosis: How is APS Detected?

Diagnosing APS requires a combination of clinical symptoms and confirmed laboratory tests. A doctor will typically order tests if a patient has had an unexplained thrombotic event or recurrent pregnancy loss.

The key to diagnosis is the persistent presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, confirmed by two positive tests at least 12 weeks apart. This waiting period is crucial to rule out temporary, non-significant elevations of these antibodies that can occur after an infection.

The main laboratory tests used are:

- Lupus Anticoagulant (LA) Test: Despite its name, this test detects antibodies that increase clotting risk. It involves sensitive coagulation tests like the dilute Russell’s viper venom time (dRVVT).

- Anticardiolipin Antibodies (aCL) Test: An ELISA test that looks for a specific type of antiphospholipid antibody.

- Anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I (aβ2GPI) Test: Another ELISA test for a key antibody associated with APS.

Treatment and Management

The primary goal of treatment is to prevent new blood clots from forming. The specific regimen depends on the individual’s history.

- For patients with thrombosis: Long-term anticoagulation therapy is standard. This often involves warfarin (Coumadin) to maintain an INR (a measure of blood thinness) between 2.0 and 3.0. Low-dose aspirin may also be used.

- For women with recurrent miscarriage: Treatment during pregnancy is highly effective and typically involves injections of heparin (which does not cross the placenta) combined with low-dose aspirin. Warfarin is avoided in pregnancy due to the risk of birth defects.

As with any condition that increases clotting risk, managing overall health is critical. This includes controlling other risk factors, such as those associated with hypertension and heart disease, and avoiding smoking and estrogen-containing birth control pills, which can further increase clot risk.

A Rare but Serious Complication

In very rare cases, patients can develop “catastrophic APS” (CAPS), a life-threatening condition where widespread small blood clots form suddenly, leading to rapid organ failure. This is a medical emergency with a high mortality rate.

For more in-depth and patient-focused information, a highly authoritative resource is the Hospital for Special Surgery’s guide to Antiphospholipid Syndrome.