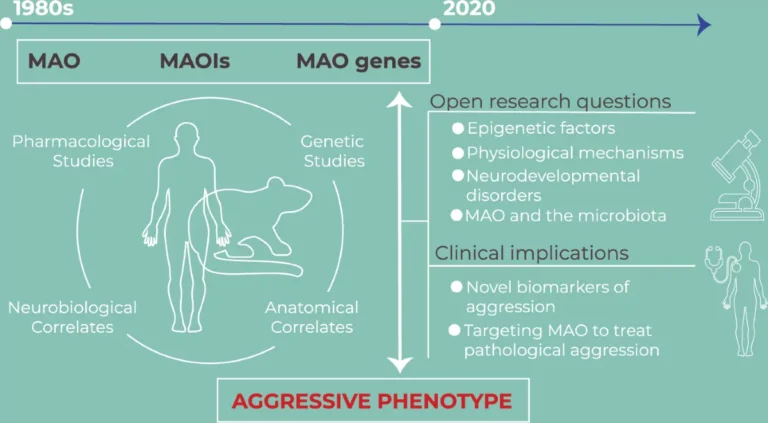

New work from criminologist Kevin Beaver (Florida State University) adds to the growing—yet nuanced—literature linking biology and behavior. His research suggests that a low-activity variant of the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA gene (MedlinePlus Genetics)) is associated with higher odds of gang involvement among men, particularly for those who experienced childhood maltreatment.

What the study found (in plain language)

Men carrying the low-activity MAOA variant were reported to be about twice as likely to join gangs as peers with the more common variant. Among men who were in gangs, those with low-activity MAOA were roughly four times as likely to report weapon use compared to men without the variant. These patterns fit prior evidence that gene–environment interactions—especially early adversity—can increase risk for aggression in a subset of men.

Important caveats

- Not destiny: Genes are risk modifiers, not fate. Most carriers of any single variant will not engage in violence.

- Context matters: Early support, skills training, prosocial peers, and stable environments can buffer biological risk.

- Older claims need caution: Historical ideas about chromosome patterns (e.g., XYY) and “innate aggression” are far from settled and should be interpreted carefully as the science evolves.

Why this matters for policy and care

Too often, persistent anger and aggression are handled primarily by the criminal justice system rather than health and social care. Containment can protect the public, but it rarely treats underlying problems with emotional regulation, trauma, or impulse control. As argued in our piece on supporting veterans—therapy, not prison—service systems should do more than punish.

If we can identify men at elevated risk early—ethically and without stigma—we can offer support before harm occurs.

Constructive, evidence-based responses

- Early intervention: Trauma-informed programs, mentoring, and family support reduce downstream risk.

- Skills training: Cognitive-behavioral approaches and anger-management protocols can help men build practical regulation strategies (see our broader discussion in Anger, Aggression and Abuse).

- Lifestyle buffers: Regular exercise and recovery practices modestly improve mood and impulse control—helpful complements to therapy (related read: Exercise Helps You Beat Depression).

Looking ahead

There have been periodic discussions about whether “aggressive behavior” should be recognized more explicitly in diagnostic systems. Regardless of labels, what’s clear is that a public-health approach—one that acknowledges biology, environment, and personal agency—can reduce harm, ease pressure on courts and prisons, and improve outcomes for men and their communities.

Bottom line: recognizing biological contributors to aggression should push us toward earlier, smarter, and more compassionate interventions—not fatalism or stigma.