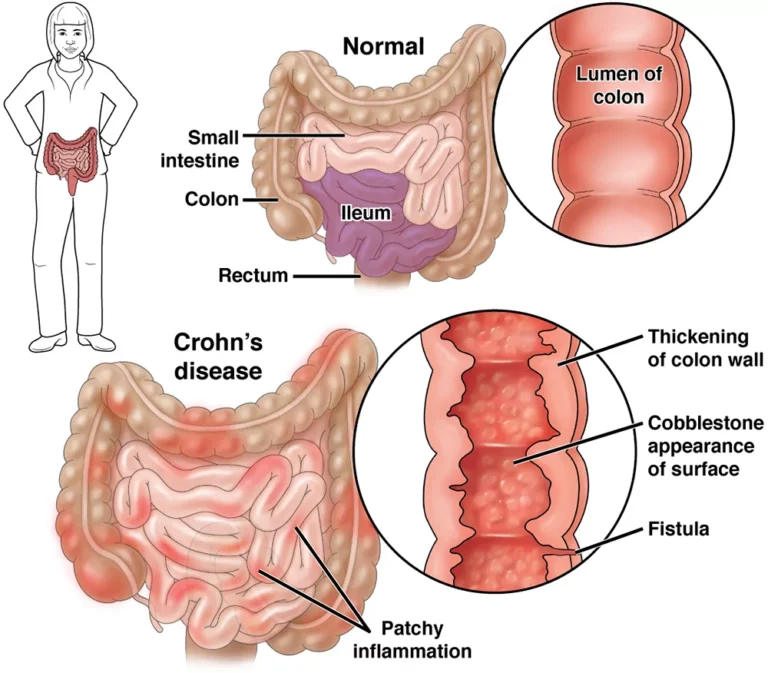

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory condition of the digestive tract. It can affect any segment from mouth to anus, most commonly the terminal ileum and/or patchy (“skip”) areas of the large bowel. Unlike irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s is an immune-mediated disease that can damage the bowel wall over time and cause complications. Ulcerative colitis is a related condition but is limited to the colon and typically involves only the inner lining; Crohn’s can involve all layers of the bowel wall.

Common Symptoms

- Persistent or recurrent diarrhea, often with urgency

- Abdominal pain and cramping, frequently in the lower right quadrant

- Unintended weight loss, fatigue, loss of appetite, low-grade fever

- Rectal bleeding (less common than in ulcerative colitis)

- Extra-intestinal features such as mouth ulcers, joint pain, skin or eye inflammation

When to seek urgent care

Severe abdominal pain, persistent high fever, repeated vomiting, signs of dehydration, or symptoms of bowel obstruction (e.g., abdominal distension, inability to pass gas/stool) warrant immediate medical attention.

Who Gets Crohn’s?

Onset is most common in the teens and twenties, but Crohn’s can start at any age and is increasingly recognized in children. Prevalence varies by region and is generally higher in industrialized countries. Family history modestly increases risk, and some ethnic groups (for example, Ashkenazi Jews) have higher rates.

Causes & Risk Factors

The exact cause is unknown. Most experts consider Crohn’s a result of an abnormal immune response in genetically susceptible individuals, influenced by environmental factors and the gut microbiome.

- Genetics: Variants in genes involved in innate immunity (e.g., NOD2/CARD15) are linked to risk, but no single gene “causes” Crohn’s.

- Environmental factors: Smoking increases the risk of Crohn’s and flares. The role of hormones (e.g., oral contraceptives) is mixed in studies.

- Microbes: Several organisms have been studied. A proposed association with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) remains unproven; research is ongoing and results are conflicting.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical evaluation and tests to both confirm inflammation and rule out infection or other causes:

- Endoscopy/colonoscopy with biopsies to identify characteristic inflammation and granulomas

- MRI or CT enterography to assess small bowel and detect strictures, fistulas, or abscesses

- Blood and stool tests (including fecal calprotectin) to gauge inflammation and exclude infections

Complications

- Strictures (narrowing) causing obstruction

- Fistulas and abscesses due to transmural inflammation

- Malnutrition, vitamin/mineral deficiencies, anemia

- Bile salt–related diarrhea after ileal involvement or resection

- Increased colorectal cancer risk with long-standing colonic disease (regular surveillance is advised)

Treatment

Therapy is individualized and often follows a treat-to-target approach (aiming for symptom control and mucosal healing). Options include:

- Corticosteroids for short-term control of flares (not for long-term maintenance due to side effects).

- Immunomodulators (azathioprine, 6-MP, methotrexate) for steroid-sparing maintenance in selected patients.

- Biologic therapies:

- Anti-TNF agents (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab)

- Anti-integrin (e.g., vedolizumab)

- Anti-IL-12/23 or selective IL-23 blockers (e.g., ustekinumab, risankizumab)

- JAK inhibitors (e.g., upadacitinib) in appropriate cases

- 5-ASA drugs have limited benefit in Crohn’s overall and are used selectively (more commonly in colonic disease).

- Antibiotics in specific situations (e.g., perianal disease, abscesses) under medical guidance.

- Nutrition therapy (including exclusive enteral nutrition in pediatrics) can induce remission for some; dietitians can help tailor plans.

- Surgery for complications such as strictures, fistulas, or disease refractory to medication. Resection or strictureplasty can relieve symptoms but is not curative; recurrence is possible.

Living Well with Crohn’s

- Stop smoking—this is one of the most impactful lifestyle changes.

- Work with your care team on vaccinations, bone health, and deficiency screening (iron, B12, vitamin D).

- Track symptoms and triggers; many people benefit from individualized nutrition strategies and stress-management techniques.

- Regular follow-up and colonoscopic surveillance for those with long-standing colonic involvement.

Differential Diagnosis

Conditions that can resemble Crohn’s include ulcerative colitis, infections, celiac disease, and IBS. If you’re exploring broader digestive wellness topics, see How Colon Care Promotes Colon Health. For another autoimmune gut condition, compare with Coeliac Disease. Long-standing inflammation also ties into general cancer prevention and surveillance—see Cancer: Causes, Types, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Prevention Guide.

History (Brief)

Although similar illnesses were described earlier, Crohn’s disease was formally characterized in 1932 by Burrill B. Crohn and colleagues as “regional ileitis,” later recognized as part of the spectrum now called inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Authoritative Resource

For patient-friendly, up-to-date guidance, see the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): NIDDK: Crohn’s Disease.

This article provides general information and is not a substitute for personalized medical advice. If you suspect Crohn’s or are experiencing a severe flare, consult a qualified clinician promptly.