Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute, immune-mediated disorder of the peripheral nervous system (nerves outside the brain and spinal cord). It often follows an infection and causes the body’s immune system to attack peripheral nerves, leading to rapidly evolving weakness, abnormal sensations, and—at its worst—breathing difficulties requiring intensive care. Older names include acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP), acute idiopathic polyneuritis, Landry’s ascending paralysis, and “French polio.”

Overview

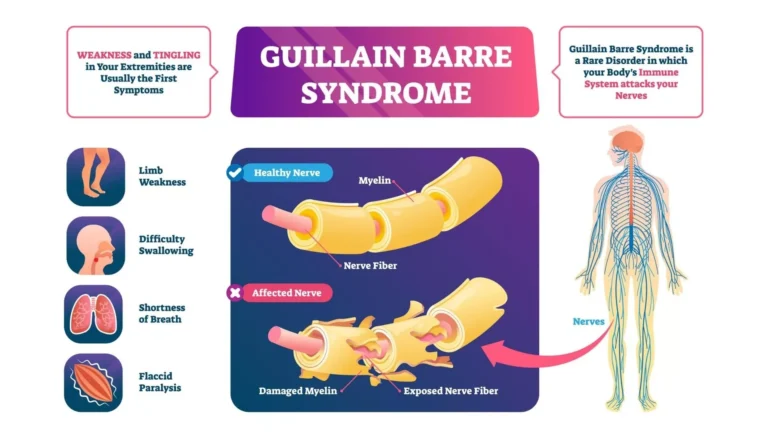

The hallmark of “classic” GBS is demyelination—loss of the myelin sheath that insulates peripheral nerves—due to an autoimmune inflammatory process. In most patients, symptoms begin days to weeks after a respiratory or gastrointestinal illness. Less commonly, GBS has followed surgery or other immune triggers. Certain infections (for example, Campylobacter jejuni) are well-recognized antecedents.

Variants exist. The commonest in many regions is AIDP (demyelinating). Axonal forms include AMAN (acute motor axonal neuropathy) and AMSAN (acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy). A distinct variant, Miller Fisher syndrome, typically causes eye movement problems, loss of reflexes, and ataxia, with relatively preserved limb strength.

Autoimmunity can target different body systems. For comparison with central nervous system demyelination, see Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM). For an example of antibody-mediated disease affecting kidneys and lungs, see Goodpasture’s Syndrome. Broader autoimmune mechanisms are also discussed in conditions like Coeliac Disease.

Prevalence

GBS is rare, affecting roughly 1–2 per 100,000 people per year. It occurs at all ages and in all sexes. True recurrences are uncommon, but they can occur years after recovery.

Causes & Triggers

- Infections: about half of patients report a preceding respiratory or gastrointestinal illness 2–4 weeks prior to symptom onset; Campylobacter jejuni, CMV, EBV, influenza, and others have been implicated.

- Other associations: recent surgery, trauma, and (less commonly) other immune triggers. A causal pathogen is not identified in many cases.

Signs & Symptoms

- Motor: progressive, usually symmetrical weakness that often starts in the legs and ascends; difficulty walking, climbing stairs, or lifting arms. Facial weakness is common.

- Sensory: tingling, numbness, painful dysesthesias; reduced vibration/position sense.

- Autonomic: swings in blood pressure, abnormal heart rate/rhythm, bowel or bladder dysfunction.

- Bulbar/respiratory: trouble swallowing, weak cough, shortness of breath. About one-third of patients may require ventilatory support during the peak phase.

Emergency signs: rapidly worsening weakness, breathing difficulty, or choking/aspiration warrant immediate medical evaluation.

Diagnosis

- Clinical assessment: pattern of progressive weakness with reduced/absent reflexes supports GBS.

- Nerve conduction studies & electromyography (EMG): show demyelination (slowed conduction, conduction block) or axonal features in AMAN/AMSAN.

- CSF (lumbar puncture): classically reveals albuminocytologic dissociation—elevated protein with normal cell count—often most evident after the first week.

- Monitoring: frequent checks of respiratory function (vital capacity), heart rhythm, and blood pressure are essential.

Treatment

Early, supportive, and disease-modifying therapy improves outcomes:

- Level-of-care: hospital admission for close monitoring; ICU if respiratory or autonomic instability develops.

- Immunotherapy: either intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) (commonly over 5 days) or therapeutic plasma exchange (PLEX). These options are similarly effective; they are not used together in routine care.

- Supportive care: DVT prophylaxis, pain control (neuropathic pain is common), careful skin care, and early physical/occupational/speech therapy.

- Corticosteroids: alone are generally not helpful in classic GBS.

Prognosis

Most patients improve after a plateau phase of weeks; recovery may take months. Approximately 80% recover the ability to walk independently, while 5–10% are left with significant disability. Despite modern care, mortality is about 2–4%, usually related to autonomic or respiratory complications.

History

The syndrome was first described by Jean Landry in 1859. In 1916, Georges Guillain, Jean-Alexandre Barré, and André Strohl identified the characteristic spinal fluid finding of high protein with few cells.

Authoritative Resource

For in-depth, patient-friendly information on diagnosis, treatment, and recovery, see the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS): NINDS – Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

This article is for general education and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Seek urgent care if weakness progresses quickly or breathing/swallowing becomes difficult.